Where once there was a row of protected carob trees, there is now an improvised wall of cinder blocks, erected around us as we sat on a tree stump.

This sudden change in space points to one of the issues coming to the surface in our three-week resistance to Infrastructure Malta’s attempts to construct a new road in Dingli. I will look at some of the intrigues that emerge from this situation, which should alarm us into rethinking our relationship with the infrastructure around us.

The road connecting Triq Dun Bosco to Daħla tas-Sienja is just one of a number of works happening in Dingli, all ‘quagmired’ between private and public uses. This is the first issue the contested road brings up: who owns what, and what right to and interest in which spaces do which persons have? Certain parts of the little stretch of land belong to one family, others to another, some are ODZ, others can be built upon, and all lie within the buffer zone of a Grade 1 Scheduled building. This whole web of ownership and protections stretching back decades is being bulldozed by IM, which is taking advantage of legal grey areas that apparently allow it to carry on without submitting its plans to public oversight.

The relationship between the residents and the road is also complex. After a lemon tree was chopped up in the early days of the action, and its fruit left unclaimed, we found ourselves supplied with a mountain of citrus we were all too happy to offer to passing supporters. On one occasion, two police officers asked us for a few lemons for one of the neighbouring street’s residents to prepare the workers some tea.

Other residents offered us figolli and plenty of nourishment as Easter Week rolled along.

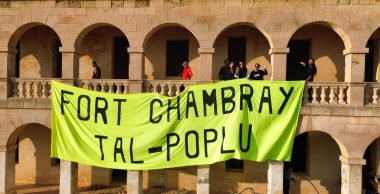

Our action in Dingli aimed to safeguard both the residents’ interests while shedding light on a broader issue that this pointless road reveals.

Claiming to have the residents’ support, Ian Borg hastily gathered a few signatures to back his claim. We responded with 250 signatures, all from people in Dingli, who backed our action.

In this way, Ian Borg’s wild claim – that of knowing everything and everyone in his hometown – quickly crumbled to pieces, especially considering his influence on Dingli. Borg and IM’s reluctance to meet and discuss the Dingli issue with all parties concerned reflects a deep discomfort, as if they are unwilling to own up to what they are really doing. Furthermore, it shows us that hidden behind the fraught image of a tight-knit community is a complex power game that mirrors what is going on in Malta as a whole.

Infrastructure Malta’s way of working reveals this. Since Dingli hit the headlines in October 2020, we still haven’t been given any clear reason as to why the road is being built at all. the excuse given was that restricted access to emergency services posed a health and safety issue — claims debunked by the Civil Protection Department, who informed us that they are adequately equipped for navigating small alleys.

Later, during the construction of the road, nobody from IM was willing to share information about the specific works being carried out. Mysterious water services, which may or may not be related to the road in question, were being installed. And, of course, the road was famously schemed in a local plan drawn up in 1965 – which begs the question as to why IM is in such a hurry to build a road planned half a century ago. The total lack of transparency is not really as suspicious as it is logical: Infrastructure Malta can keep us in the dark in a stark and shameless display of just how much power it has.

IM’s excessive power belies this whole issue. Beyond the simple loss of 300-year old trees, tilled agricultural land and cultural heritage, our resistance to this road equals our resistance to IM’s power to work without consultation and permits, for the benefit of the few who stand to gain by speculating on future constructions. Infrastructure manifests in the real world the abstract speculation of economics; in so doing changing how we can relate to the space around us. Our very movements are directed through gates, fences, bollards and a complete lack of communication with the people who are considered as “biċċa ċittadin”.

Infrastructure Malta, Ian Borg and a few interested parties are taking advantage of a complex web of ownerships, while creating cracks in the community to allow them to exert their power.

So what can we do?

A few years ago, in the wake of the Occupy demonstrations around the world, a wave of optimism spread that encouraged people to attempt to decentralise and democratise infrastructure itself, taking public spaces into their own hands and using them for the genuine good of the community.

Neoliberalism in the West has accelerated at such a fast rate that it feels like every small attempt at this is quashed before it can make the vital step from an idea into an intervention in public space.

But for those three weeks, we held out and stood up to power and greed. And we have no trouble doing the same thing again.

Noah Fabri is a member of Moviment Graffitti