There’s no denying that the sight of heavy machinery turning up unexpectedly at your doorstep, no later than seven in the morning, is not the way you’d expect your weekend to start.

Residents of an alley in Dingli were treated exactly to this kind of spectacle as Infrastructure Malta’s heavyweights appeared out of nowhere and, without warning, expected to tear down a private wall and rip straight through a farmer’s field, with the intention of building a road.

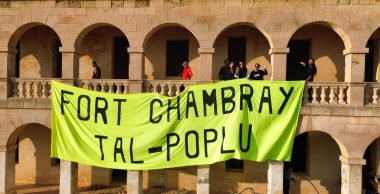

Flanked by the residents, we intervened to stop this first assault.

Someone at Infrastructure Malta must have a morbid sense of humour. Or, maybe, some of the big cheeses believe they’re in China, where bulldozers appear without notice to rip through your house and livelihood, offering no right to redress.

Dingli was not the first example of Infrastructure Malta taking the law in their hands. We’ve seen similar cases.

For starters, Wied Qirda: a grand debacle where Infrastructure Malta decided to tarmac a rural pathway, build a bridge, ruin the water flow, and ignore an ERA stop-and-comply order – since all this was done without a permit.

They did so at unnatural speed and carelessness. One of their trucks ended belly-up in the valley, splattering tarmac all over pristine land.

Then came Central Link, where Infrastructure Malta ignored a pending court case and commenced works, forcing the court to find against the residents’ lawsuit but not without condemning the agency for the way it went ahead with its works.

Residents and farmers also got the short end of the stick with reports of bullying from contractors, residents being locked in their streets for a week and farmers losing access to fields, water and loss of wells and rooms.

All this was done with the efficiency and ruthlessness of a Panzer division on its way to Warsaw.

Tal-Balal was another textbook case of Infrastructure Malta widening a road without having the necessary permits; either because the government finds its own paperwork must really be a burden or else because somebody feels above the law and able to get away with it.

There is, however, one man in all this who knows a thing or two about the Chinese.

Frederick Azzopardi, Infrastructure Malta supremo and right hand to Infrastructure Minister Ian Borg (although I am sometimes confused as to who answers to who here), was also the head of energy regulator ARMS, where he worked alongside Konrad Mizzi at a time when Malta was signing the infamous Electrogas contract and revamping its “kitchen cabinet.”

Shortly afterwards, he abandoned Mizzi, riding as Borg’s favourite knight and rapidly asserting himself as one of the chessboard’s most creative freewheelers. Rules, thus, became a nuisance for Azzopardi, who, as many other pieces on the board will attest, moves in whatever way he pleases.

Don’t mistake it for flair, however. Azzopardi is an expert at cutting corners, sometimes literally, and with the backing of a tarmac-hungry minister, road building has become the new ‘in’ thing.

Think of it as an expensive piece of propaganda for a beleaguered minister trying to beef up his status, shortly after being shut out of the deputy leader contest within Labour and losing the planning portfolio.

There’s a commercial pretext for roadbuilding. Traditionally, new buildings spring alongside a new road and this is also true of Malta. The tarmac on Tal-Balal still hadn’t set when two applications for two supermarkets appeared out of nowhere; and the same happened with Central Link, which spawned two supermarket applications in Attard and Żebbuġ respectively. As it happens, now that the fuel station glut has been killed by a policy reform (which never saw the light under Borg’s domain of the PA), new roads and supermarkets have become the new grail.

Azzopardi is a sturdy piece of furniture for any cabinet, stronger than your average IKEA. He has no lack of confidence in venturing out on bulldozing expeditions such as the one we saw last week in Dingli.

As it happened, we soon found out that the road would have not only stolen land and livelihood from a farmer but also threatened the structural integrity of a late medieval chapel and the immediate context.

I find it strange that a minister responsible for planning never found the time to schedule a historical gem in his own rural home town, considering the song and dance he makes every time a few trees are planted after each massacre.

Besides this, of course, were the elements of speed and silence with which the roads agency descended on to Dingli. The minister, and Azzopardi, badly want this road project to happen quickly.

But then another thing baffles me.

Borg sent out a leaflet to residents of Dingli in the immediate aftermath, justifying the project with six very debatable points (which we have rebutted last week).

Now, I’ve never seen a minister trusted with the super-projects portfolio take time out to advertise a road joining two alleys and distribute the flyers within a week. Again, why so fast?

It’s purely symptomatic of Borg’s behaviour; there are parallels with the hurried land grab of Miżieb and L-Aħrax, which he and his Lands Department authored to appease the FKNK.

One thing I’m certain of, however, is that Infrastructure Malta’s bullying has reached apocalyptic heights. The bull-in-the-China-shop attitude adopted by Borg and Azzopardi reminds me of a former public works minister whose name brings thousands of teeth across Malta to a violent clench.

That name is Lorry Sant.

The prime minister, who knows his party’s history, surely cannot afford another one in his cabinet.

Wayne Flask is a member of Moviment Graffitti.